Rosaura Revueltas

Rosaura Revueltas | |

|---|---|

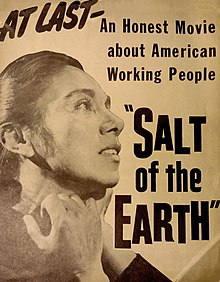

Revueltas in the poster for Salt of the Earth (1954) | |

| Born | August 6, 1910 Lerdo, Durango, Mexico |

| Died | April 30, 1996 (aged 85) Cuernavaca, Mexico |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1950–1977 |

Rosaura Revueltas Sánchez (August 6, 1910 – April 30, 1996) was a Mexican actress of screen and stage, and a dancer, author and teacher.

Early life

[edit]Rosaura Revueltas was born in Lerdo, Durango, Mexico in 1910 to the famously artistic Revueltas family and had three brothers who were artists: Silvestre Revueltas a composer, José Revueltas a writer, and Fermín Revueltas a painter.[1] The family moved to Mexico City in 1921, and Rosaura enrolled in the Humboldt School, where she learned German and English. She also studied ballet and acting.[2]

Like her brothers, Rosaura chose a profession in the arts. She had her first success on stage in La desconocida de Arras (1946). By 1950, she was starring in El cuadrante de la soledad. Although she continued to do some theatrical work such as Edmundo Baez's play Un Alfiler en los Ojos (1952), Revueltas turned her attention in 1950 to film acting, culminating in her best-known film Salt of the Earth (1954) in the United States.

Film career

[edit]In 1950, Revueltas landed a minor part in Pancho Villa vuelve (1950). She then earned a more prominent role in Un día de vida (1950). She portrayed Rosa Suárez, viuda de Ortiz (the widow of Ortiz), in Las Islas Marías (1951), featuring Pedro Infante. The following year, she was in El rebozo de Soledad, and in 1953 she played Tia Magdalena in the American-made film Sombrero.[3]

In 1951, Revueltas began a pattern of selecting roles in politically charged films when she starred as the "Madre superiora" in Muchachas de Uniforme. It was the Mexican remake of the 1931 German film Mädchen in Uniform, which was one of the first screen representations of lesbian romance. Her willingness to choose pathbreaking projects sometimes caused her to be targeted by politicians and Catholic Church officials. After the release of Muchachas de Uniforme, the Catholic Church urged a boycott of the film.[4] In the aftermath of the controversy, Revueltas immigrated to the U.S and continued to gravitate toward roles that offered progressive representations of women when she landed the main part in Herbert J. Biberman's Salt of the Earth (1954).[5]

The story was based on the 1951 Empire Zinc strike in Grant County, New Mexico. She played Esperanza Quintero, the wife of a mine worker. In the film, Esperanza's husband and fellow miners decide to go on strike, and in turn, their wives do the same in order to support their spouses and gain rights of their own.[6]

Revueltas was not Biberman's first choice for Esperanza. Originally his wife Gale Sondergaard was cast, but upon further reflection, Biberman thought the role should be portrayed by a Spanish-speaking actress.[7] Revueltas was one of the few professional actors in Salt of the Earth. Most of the other roles, including that of her husband Ramon, were played by actual miners, some of whom had taken part in real-life strikes. For example, Juan Chacón, who played Ramon Quintero, was the president of a local miners' union.[8]

Blacklisted

[edit]The Hollywood blacklist and Red Scare cast a shadow over Salt of the Earth. The film's director Herbert Biberman was a member of the Hollywood Ten, the group of film artists blacklisted for refusing to cooperate with the House Committee on Un-American Activities. His Academy Award-winning actress wife Gale Sondergaard supported Biberman throughout this time period, and she was blacklisted as well. The film's writer Michael Wilson and producer Paul Jarrico were also blacklistees. Because of her involvement in Salt of the Earth, Revueltas became a blacklistee too.[9]

Near the end of filming on February 25, 1953, Revueltas was arrested by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) on an alleged passport violation (not having it stamped properly upon entry to the country).[10] She was taken from the filming location in Silver City, New Mexico and driven 150 miles to El Paso, Texas. During the drive, she was repeatedly asked if she was a Communist and if her friends were Communists. "She said she didn't know, that she was just working on the picture, and she hummed. In El Paso she was kept under armed guard in a hotel room."[11] As a result of her incarceration, at least one scene was filmed by a Revueltas stand-in with her back to the camera. Esperanza's voice-over narration had to be taped later in Mexico.[12]

Revueltas was released from custody on March 6, 1953 and could return to Mexico, but she was never allowed to work in American films again. She once said that "[s]ince [the INS] had no evidence to present of my 'subversive' character, I can only conclude that I was 'dangerous' because I had been playing a role that gave status and dignity to the character of a Mexican-American woman."[13]

While Salt of the Earth was restricted to a very limited release and garnered almost no publicity, it did receive mild praise from Bosley Crowther of The New York Times. He called it

a strong pro-labor film with a particularly sympathetic interest in the Mexican-Americans with whom it deals. True, it frankly implies that the mine operators have taken advantage of the Mexican-born or descended laborers, have forced a "speed up" in their mining techniques and given them less respectable homes than provided the so-called "Anglo" laborers. It slaps at brutal police tactics in dealing with strikers and it gets in some rough, sarcastic digs at the attitude of "the bosses" and the working of the Taft–Hartley Law.[14]

Salt of the Earth was the only film to be blacklisted during the McCarthyism period of the 1950s.[15][16] Because the work was largely unknown in North America except for cult interest, Revueltas was not given full recognition for her acting achievement (note: she did win Best Actress in 1954 at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the former Czechoslovakia[17]). Then, in the 1980s, Turner Classic Movies began showing the movie; film critics and scholars began writing about it; and it started to be seen by more and more people. In 1992, nearly 40 years after being suppressed, Salt of the Earth was inducted into the Library of Congress's National Film Registry of significant U.S. films.[16]

Later years

[edit]Unable to get hired in the U.S. or Mexico, Revueltas moved to East Germany in 1957 and lived there until 1960. While in East Germany, she worked with the Berliner Ensemble—the company of the late playwright Bertolt Brecht. She also worked briefly in Cuba. She returned to Mexico in 1960 and found herself in difficult financial straits.[9] She taught dance and began to write plays.[18] It wasn't until 1976 that she made her first film since being blacklisted, Mina, viento de libertad (Mina, Wind of Freedom). In that same year, she played Tía Licha in Lo Mejor de Teresa (The Best of Teresa). Her final film was Balun Canan (1977). In 1979, she published the book Los Revueltas: Biografía de una familia (The Revueltas: Biography of a Family).[5] She served occasionally as a judge in film festivals, including the 36th Berlin International Film Festival in 1986.[19] In her later years, she resided in Cuernavaca and taught hatha yoga.[9]

Death

[edit]She died in Cuernavaca on April 20, 1996, six months after having been diagnosed with lung cancer, at age 85. She was survived by her only child, a son, Arturo Bodenstedt.[5][18]

Awards

[edit]She won Mejor Papel de Cuadro Femenino (Best Actress in a Minor Role) at Mexico's 1953 Ariel Awards for her work in El rebozo de Soledad. In 1954, the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival conferred its Best Actress Award on Revueltas for Salt of the Earth.[17]

Legacy

[edit]In 2000, the film One of the Hollywood Ten was released. Written and directed by Karl Francis, it's a dramatization of Herbert Biberman's blacklist experience, and includes a segment on Salt of the Earth in which Revueltas is portrayed by actress Ángela Molina.

Selected filmography

[edit]- Pancho Villa vuelve, a.k.a. Pancho Villa Returns (1950)

- Del odio nace el amor, a.k.a. The Torch (1950)

- Un Día de Vida, a.k.a. One Day of Life (1950)

- Muchachas de Uniforme, a.k.a. Girls in Uniform (1951)

- Las Islas Marías (1951)

- El Cuarto Cerrado (1952)

- El rebozo de Soledad (1952)

- Sombrero (1953)

- Salt of the Earth (1954)

- Mina, Viento de Libertad, a.k.a. Mina, Wind of Freedom (1976)

- Lo Mejor de Teresa (1976)

- Balún Canán (1976)

References

[edit]- ^ Gonzalez Cruz, Maricela. "Fermin Revueltas" (PDF). Revista de la Universidad de UNAM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Martinez, Roberto Chapa (6 September 2024). "Rosaura Revueltas". Regio.com.

- ^ "Rosaura Revueltas (1910-1996)". IMDb.

- ^ Aguilar, Carlos. "This Rarely Seen 1951 Mexican Film Boldly Tells a Lesbian Love Story". Remezcla. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Oliver, Myrna (3 May 1996). "Rosaura Revueltas; Blacklisted Over Film". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Grimes, William (2 May 1996). "Rosaura Revueltas, 86, the Star Of a Pro-Labor Film of the 50s". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Salt of the Earth at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films.

- ^ Lorence, James J. (1999). The Suppression of Salt of the Earth: How Hollywood, Big Labor, and Politicians Blacklisted a Movie in Cold War America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8263-2028-7.

- ^ a b c Lorence 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Lorence 1999, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Miller, Tom (1984). "Class Reunion: 'Salt of the Earth' Revisited". Cinéaste. 13 (3): 30–36.

- ^ "Notes for Salt of the Earth". TCM.

- ^ Lorence 1999, p. 83.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (15 March 1954). "Movie Review: The Screen in Review; ' Salt of the Earth' Opens at the Grande -- Filming Marked by Violence". The New York Times. Retrieved 2018-02-24.

- ^ Lorence 1999, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b McNearney, Allison (26 June 2022). "The Insane Saga of 'Salt of the Earth,' the Only Film to Be Blacklisted". Daily Beast.

- ^ a b "Rosaura Revueltas - Awards". IMDb.

- ^ a b Marion, Don; Bellinger, Guy. "Rosaura Revueltas - Mini Bio". IMDb.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1986 Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-01-14.

Further reading

[edit]- Crowther, Bosley (April 23, 1953). "'Sombrero' Skims into Loew's State and a Resolute Cast is Obscured by the Shade". The New York Times.

- Crowther, Bosley (March 15, 1954). "'Salt of the Earth' opens at the Grande - Filming Marked by Violence". The New York Times.

- Lorence, James J. The Suppression of 'Salt of the Earth'. How Hollywood, Big Labor, and Politicians Blacklisted a Movie in Cold War America, University of New Mexico Press: 1999 (ISBN 0-8263-2027-9 - cloth version/ISBN 0-8263-2028-7 - paper version)

50 años de Danza, Palacio de Bellas Artes. Vol. I y II. México: INBA/SEP, 1985.

50 años de Ópera, Palacio de Bellas Artes. México: INBA/SEP, 1986.

50 años de Teatro, Palacio de Bellas Artes. México: INBA/SEP, 1986.

Azar, Héctor. Funciones Teatrales. México: SEP/CADAC, 1982.

Bake’s Biografical Dictionary of Musicians. 8a. Ed. Revisada por Nicolás Slonimsky. New York: Schirmer Books, 1992.

Careaga, Gabriel. Sociedad y Teatro Moderno en México. México: Contrapuntos, 1994.

Ceballos, Edgar. Diccionario Enciclopédico Básico de Teatro Mexicano. Col. Escenología. México: Siglo XX, 1996.

---. Las Técnicas de Actuación en México. Colección Escenología. México: Gaceta, 1993.

Encyclopaedia Britannica de México. Lexipedia Barsa. Tomo II. México: 1984.

Enciclopedia de México. Dir. José Rogelio Álvarez. Tomo 1, 7, 8, 9, 10, y 13. México: S.E.P./Enciclopedia de México, 1987.

García Riera, E., Macotela, F. La Guia del Cine Mexicano. 1919-1984. México: Patria, 1985

García Riera, Emilio. Historia Documental del Cine Mexicano. Tomo IV (1949-1951). México: Era, 1972.

---. Historia Documental del Cine Mexicano. Tomo V (1952-1954). Tomo VII (1955-1957). México: Era, 1973.

---. Historia Documental del Cine Mexicano. Tomo 4 (1946-1948). Tomo 5 (1949-1950). Tomo 6 (1951-1952). Tomo 7 (1953-1954). México: Universidad de Guadalajara et. al., 1993.

---. Historia Documental del Cine Mexicano. Tomo 17 (1974-1976). México: Universidad de Guadalajara et. al., 1995.

Garraty, John A. The nature of biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1957.

Gorostiza, Celestino. Teatro mexicano del S. XX. México: FCE, 1956.

Hernández Camargo, Emiliano. Durangueñeidad, el orgullo de lo nuestro. Durango: Dirección General de Culturas Populares Unidad Regional Norte La Laguna, 1997.

Hernández, Ignacio. Prólogo en Revueltas, José. El cuadrante de la soledad (y otras obras de teatro). No. 21. Andrea Revueltas y Philippe Cheron recop. y notas. México: Era, 1984.

Hernández Sampieri, et. al. Metodología de la Investigación. Colombia: McGraw Hill, 1991.

Johnson, Rodrigo ed. Brecht en México a cien años de su nacimiento México: U.N.A.M./La Compañía Perpetua/ I.N.B.A., C.I.T.R.U., 1998.

Kschemisvara; Hsing-Tao, Li. La ira de caúsica y El círculo de tiza Buenos Aires: Espasa-Calpe, 1941.

Leyva, José Angél. El Naranjo en Flor (Homenaje a los Revueltas). Juan Pablos y el Instituto Municipal del Arte y la Cultura eds. 2a. Ed. México: Sin Nombre, 1999.

Lozoya Cigarroa, Manuel. Historia Mínima de Durango. Durango: Ed. Durango, 1995.

---. Hombre y Mujeres de Durango. 2a. Ed. Durango: Comisión de Estudios Históricos e Investigaciones Sociales del Estado de Durango-PRI, 1985.

Magaña Esquivel, Antonio, y Ruth S. Lamb. Breve Historia del Teatro Mexicano. México: Andrea, 1958.

Magaña Esquivel, Antonio. Medio Siglo de Teatro Mexicano [1900-1961]. México: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 1964.

---. Teatro Mexicano del Siglo XX. Vol. II. México: FCE, 1986.

May, Georges. La autobiografía. Trad. Danubio Torres Fierro. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1982.

Murray Kendall, Paul. The art of biography. New York: Norton & Co., 1965.

de Olavarria y Ferrari, Enrique. Reseña Histórica del Teatro en México Tomo V. 3a. Ed. México: Porrúa, 1961.

Pâris, Alain. Diccionario de Intérpretes. Trad. Juan Sainz de los Terreros. Madrid: Turner Música, 1985.

Revueltas, José. Cuestionamientos e intenciones No. 18. 2a. Ed. Andrea Revueltas y Philippe Cheron recop. y notas. México: Era, 1981.

---. El cuadrante de la soledad (y otras obras de teatro). No. 21. Andrea Revueltas y Philippe Cheron recop. y notas. México: Era, 1984.

---. El cuadrante de la soledad. México: Novaro, 1971.

---. Las Evocaciones Requeridas. Vol. I y II. Andrea Revueltas y Philippe Cheron recop. y notas. México: Era, 1987.

Revueltas, Rosaura. Los Revueltas. México: Grijalbo, 1979.

---. Silvestre Revueltas por él mismo. México: Era, 1989.

Testimonios para la Historia del Cine Mexicano. IV. Cuadernos de la Cineteca Nacional. Dir. General de Cinematografía et. al. México: Secretaría de Gobierno, 1976.

Völker, Klaus. Brecht: a Biography. Trad. John Norwell. New York: Seabury Press, 1978.